An enchanted Game-Land

European music and Indonesian music existed, for a long time, without ever meeting. When the encounter finally occurred, each music was predictably judged by the other party as being strange and remote. This was true of the majority of opinions – especially in Nineteenth Century Europe, an era convinced of its own superiority. We must, however, notice that two of the most influential musicians of their time and culture – Debussy and Bartók – were able to “hear” in the most concrete and humble way (through audition) and in the most subtle of ways (through comprehension) the essence and universality of such faraway music. When Debussy discovered Indonesian music in 1889, such a world of sound was hardly considered. It was also barely archived in museum collections when Bartók sought this music in the 1920s and 1930s.

Both creators – among the most original and innovative composers of their times – approached Indonesian music in two different ways. We shall attempt to understand each composer’s journey and outcomes.

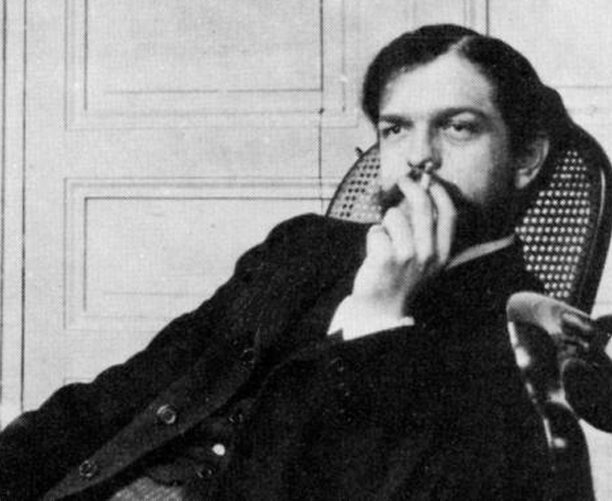

A Chiming Keyboard – Debussy

The fact that Debussy discovered Sundanese gamelan music at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1889 is established and undisputed. But it also “entered in the legend” and this is admitted without additional scrutiny. This means that we easily omit to ask ourselves how Debussy came to such a discovery, what was the concrete impact of such a revelation, and which personal experiences – intimate, organic and sensual – led him to find the profound meaning of gamelan music, at a time when nearly everyone around him only heard a hodgepodge of metallic bells rung by submissive and colonized tribes. On the one hand, what happened then wasn’t the intellectual illumination of a prophet, or of a solely spiritual being: it came from the experience of a body and a soul. For, what Debussy heard that day, he heard it with his musician’s ear, but he also, and more importantly, perceived it with the heart, nerves, sex and brain of a living and breathing man.

And, on the other hand, in order for him to « hear » such great music, he had to be Achille-Claude Debussy, and couldn’t be anyone else. The entire creative approach could only be embodied by him, as his path had begun in childhood, and as he was guided by intelligence and intuition, both of those qualities being united and advancing together.

2 – From the Island of Bali – Bartók (2)

One had to be born Hungarian in 1881 and be the subject of an Empire dominated by German language and culture to travel on a donkey’s back in 1905 and collect the marvellous popular songs and dances that still rhythmed the lives of farmers and mountain people in remote regions of Hungary, Romania and the Balkans. One had to be Hungarian, determined, inflexible and conscious of being on a historical mission: to save from oblivion a heritage that couldn’t remain alive, if it weren’t for audacious composers who could recreate it.

One of the most characteristic aspects of Bartók’s music, alongside his integration and transformation of popular themes and rhythms, has to do with the way in which he opposes two complementary harmonic worlds (7): the first is chromatic and generates circular movements, leading to spiralling effects, as if it were driven by strong churning. The second is diatonic and conveys linear thrusts, bursts of ascending lines of triumphant expression. His most sophisticated works are the result of this opposition. In the first movement of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (1937), as well as in the third movement (8), we are able to follow this struggle and to witness each harmonic world’s mutual intensification.